-

Agriculture

Agriculture

-

Health-Care

Health-Care

-

Environment

Environment

-

Construction-Real-Estate

Construction-Real-Estate

-

Tools-Hardware

Tools-Hardware

-

Home-Garden

Home-Garden

-

Furniture

Furniture

-

Luggage-Bags-Cases

Luggage-Bags-Cases

-

Medical-devices-Supplies

Medical-devices-Supplies

-

Gifts-Crafts

Gifts-Crafts

-

Sports-Entertainment

Sports-Entertainment

-

Food-Beverage

Food-Beverage

-

Vehicles-Transportation

Vehicles-Transportation

-

Power-Transmission

Power-Transmission

-

Material-Handling

Material-Handling

-

Renewable-Energy

Renewable-Energy

-

Safety

Safety

-

Testing-Instrument-Equipment

Testing-Instrument-Equipment

-

Construction-Building-Machinery

Construction-Building-Machinery

-

Pet-Supplies

Pet-Supplies

-

Personal-Care-Household-Cleaning

Personal-Care-Household-Cleaning

-

Vehicle-Accessories-Electronics-Tools

Vehicle-Accessories-Electronics-Tools

-

School-Office-Supplies

School-Office-Supplies

-

Packaging-Printing

Packaging-Printing

-

Mother-Kids-Toys

Mother-Kids-Toys

-

Business-Services

Business-Services

-

Commercial-Equipment-Machinery

Commercial-Equipment-Machinery

-

Apparel-Accessories

Apparel-Accessories

-

Security

Security

-

Shoes-Accessories

Shoes-Accessories

-

Vehicle-Parts-Accessories

Vehicle-Parts-Accessories

-

Jewelry-Eyewear-Watches-Accessories

Jewelry-Eyewear-Watches-Accessories

-

Lights-Lighting

Lights-Lighting

-

Fabric-Textile-Raw-Material

Fabric-Textile-Raw-Material

-

Fabrication-Services

Fabrication-Services

-

Industrial-Machinery

Industrial-Machinery

-

Consumer-Electronics

Consumer-Electronics

-

Electrical-Equipment-Supplies

Electrical-Equipment-Supplies

-

Electronic-Components-Accessories-Telecommunications

Electronic-Components-Accessories-Telecommunications

-

Home-Appliances

Home-Appliances

-

Beauty

Beauty

-

Chemicals

Chemicals

-

Rubber-Plastics

Rubber-Plastics

-

Metals-Alloys

Metals-Alloys

- Masonry Materials

- Curtain Walls & Accessories

- Earthwork Products

- Fireproofing Materials

- Heat Insulation Materials

- Plastic Building Materials

- Building Boards

- Soundproofing Materials

- Timber

- Waterproofing Materials

- Balustrades & Handrails

- Bathroom & Kitchen

- Flooring & Accessories

- Tiles & Accessories

- Door, Window & Accessories

- Fireplaces & Stoves

- Floor Heating Systems & Parts

- Stairs & Stair Parts

- Ceilings

- Elevators & Escalators

- Stone

- Countertops, Vanity Tops & Table Tops

- Mosaics

- Metal Building Materials

- Multifunctional Materials

- Ladders & Scaffoldings

- Mouldings

- Corner Guards

- Decorative Films

- Formwork

- Building & Industrial Glass

- Other Construction & Real Estate

- Wallpapers/Wall panels

- HVAC System & Parts

- Outdoor Facilities

- Prefabricated Buildings

- Festive & Party Supplies

- Bathroom Products

- Household Sundries

- Rain Gear

- Garden Supplies

- Household Cleaning Tools & Accessories

- Lighters & Smoking Accessories

- Home Storage & Organization

- Household Scales

- Smart Home Improvement

- Home Textiles

- Kitchenware

- Drinkware & Accessories

- Dinnerware, Coffee & Wine

- Home Decor

- Golf

- Fitness & Body Building

- Amusement Park Facilities

- Billiards, Board Game,Coin Operated Games

- Musical Instruments

- Outdoor Affordable Luxury Sports

- Camping & Hiking

- Fishing

- Sports Safety&Rehabilitation

- Ball Sports Equipments

- Water Sports

- Winter Sports

- Luxury Travel Equipments

- Sports Shoes, Bags & Accessories

- Cycling

- Other Sports & Entertainment Products

- Artificial Grass&Sports Flooring&Sports Court Equipment

- Scooters

- Food Ingredients

- Honey & Honey Products

- Snacks

- Nuts & Kernels

- Seafood

- Plant & Animal Oil

- Beverages

- Fruit & Vegetable Products

- Frog & Escargot

- Bean Products

- Egg Products

- Dairy Products

- Seasonings & Condiments

- Canned Food

- Instant Food

- Baked Goods

- Other Food & Beverage

- Meat & Poultry

- Confectionery

- Grain Products

- Feminie Care

- Hair Care & Styling

- Body Care

- Hands & Feet Care

- Hygiene Products

- Men's Grooming

- Laundry Cleaning Supplies

- Travel Size & Gift Sets

- Room Deodorizers

- Other Personal Care Products

- Pest Control Products

- Special Household Cleaning

- Floor Cleaning

- Kitchen & Bathroom Cleaning

- Oral Care

- Bath Supplies

- Yellow Pages

- Correction Supplies

- Office Binding Supplies

- Office Cutting Supplies

- Board Erasers

- Office Adhesives & Tapes

- Education Supplies

- Pencil Cases & Bags

- Notebooks & Writing Pads

- File Folder Accessories

- Calendars

- Writing Accessories

- Commercial Office Supplies

- Pencil Sharpeners

- Pens

- Letter Pad/Paper

- Paper Envelopes

- Desk Organizers

- Pencils

- Markers & Highlighters

- Filing Products

- Art Supplies

- Easels

- Badge Holder & Accessories

- Office Paper

- Printer Supplies

- Book Covers

- Other Office & School Supplies

- Stationery Set

- Boards

- Clipboards

- Stamps

- Drafting Supplies

- Stencils

- Electronic Dictionary

- Books

- Map

- Magazines

- Calculators

- Baby & Toddler Toys

- Educational Toys

- Classic Toys

- Dress Up & Pretend Play

- Toy Vehicle

- Stuffed Animals & Plush Toys

- Outdoor Toys & Structures

- Balloons & Accessories

- Baby Food

- Children's Clothing

- Baby Supplies & Products

- Maternity Clothes

- Kids Shoes

- Baby Care

- Novelty & Gag Toys

- Dolls & Accessories

- Puzzle & Games

- Blocks & Model Building Toys

- Toddler Clothing

- Baby Clothing

- Kids' Luggage & Bags

- Arts, Crafts & DIY Toys

- Action & Toy Figures

- Baby Appliances

- Hobbies & Models

- Remote Control Toys

- Promotional Toys

- Pregnancy & Maternity

- Hygiene Products

- Kid's Textile&Bedding

- Novelty & Special Use

- Toy Weapons

- Baby Gifts

- Baby Storage & Organization

- Auto Drive Systems

- ATV/UTV Parts & Accessories

- Marine Parts & Accessories

- Other Auto Parts

- Trailer Parts & Accessories

- Auto Transmission Systems

- Train Parts & Accessories

- Universal Parts

- Railway Parts & Accessories

- Auto Brake Systems

- Aviation Parts & Accessories

- Truck Parts & Accessories

- Auto Suspension Systems

- Auto Lighting Systems

- New Energy Vehicle Parts & Accessories

- Auto Steering Systems

- Wheels, Tires & Accessories

- Bus Parts & Accessories

- Auto Performance Parts

- Cooling System

- Go-Kart & Kart Racer Parts & Accessories

- Air Conditioning Systems

- Heavy Duty Vehicle Parts & Accessories

- Auto Electrical Systems

- Auto Body Systems

- Auto Engine Systems

- Container Parts & Accessories

- Motorcycle Parts & Accessories

- Refrigeration & Heat Exchange Equipment

- Machine Tool Equipment

- Food & Beverage Machinery

- Agricultural Machinery & Equipment

- Apparel & Textile Machinery

- Chemical Machinery

- Packaging Machines

- Paper Production Machinery

- Plastic & Rubber Processing Machinery

- Industrial Robots

- Electronic Products Machinery

- Metal & Metallurgy Machinery

- Woodworking Machinery

- Home Product Manufacturing Machinery

- Machinery Accessories

- Environmental Machinery

- Machinery Service

- Electrical Equipment Manufacturing Machinery

- Industrial Compressors & Parts

- Tobacco & Cigarette Machinery

- Production Line

- Used Industrial Machinery

- Electronics Production Machinery

- Other Machinery & Industrial Equipment

- Camera, Photo & Accessories

- Portable Audio, Video & Accessories

- Television, Home Audio, Video & Accessories

- Video Games & Accessories

- Mobile Phone & Accessories

- Electronic Publications

- Earphone & Headphone & Accessories

- Speakers & Accessories

- Smart Electronics

- TV Receivers & Accessories

- Mobile Phone & Computer Repair Parts

- Chargers, Batteries & Power Supplies

- Used Electronics

- VR, AR, MR Hardware & Software

- Projectors & Presentation Equipments

- Other Consumer Electronics

- Cables & Commonly Used Accessories

- Computer Hardware & Software

- Displays, Signage and Optoelectronics

- Discrete Semiconductors

- Wireless & IoT Module and Products

- Telecommunications

- Connectors, Terminals & Accessories

- Development Boards, Electronic Modules and Kits

- Circuit Protection

- Sensors

- Isolators

- Audio Components and Products

- Integrated Circuits

- Power Supplies

- Relays

- RF, Microwave and RFID

- Electronic Accessories & Supplies

- Passive Components

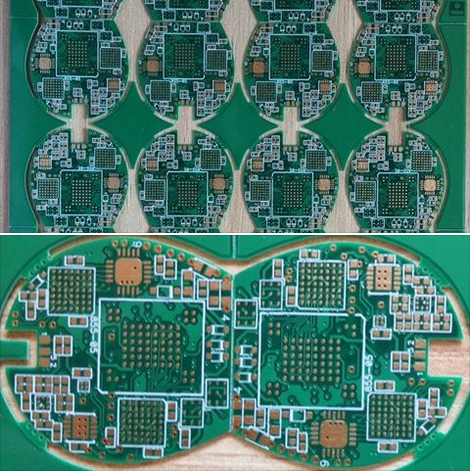

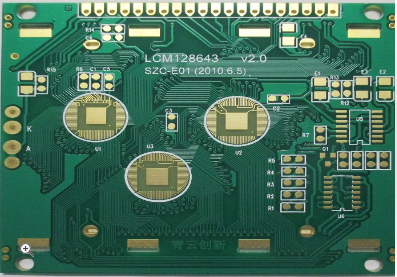

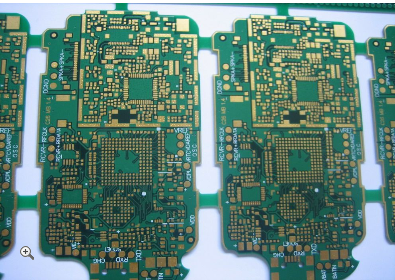

- PCB & PCBA

- Air Quality Appliances

- Home Appliance Parts

- Heating & Cooling Appliances

- Small Kitchen Appliances

- Laundry Appliances

- Water Heaters

- Water Treatment Appliances

- Refrigerators & Freezers

- Personal Care & Beauty Appliances

- Major Kitchen Appliances

- Cleaning Appliances

- Second-hand Appliances

- Smart Home Appliances

- Other Home Appliances

- Energy Chemicals

- Inorganic Chemicals

- Basic Organic Chemicals

- Agrochemicals

- Admixture & Additives

- Catalysts & Chemical Auxiliary Agents

- Pigments & Dyestuff

- Coating & Paint

- Daily Chemicals

- Polymer

- Organic Intermediate

- Adhesives & Sealants

- Chemical Waste

- Biological Chemical Products

- Surface Treatment Chemicals

- Painting & Coating

- Chemical Reagents

- Flavor & Fragrance

- Non-Explosive Demolition Agents

- Other Chemicals

- Custom Chemical Services

High Frequency Considerations In RF And Microwave Electronics Layout Design

In the rapidly advancing world of wireless communication, radar systems, and satellite technology, the design and layout of Radio Frequency (RF) and Microwave electronics stand as a critical frontier between theoretical performance and practical, reliable operation. While low-frequency circuit design often treats interconnections as ideal, zero-resistance paths, this assumption catastrophically fails at gigahertz frequencies. Here, the physical layout of components and traces on a printed circuit board (PCB) becomes an integral part of the circuit itself, directly influencing impedance, signal integrity, noise, and overall system efficiency. "High Frequency Considerations in RF and Microwave Electronics Layout Design" delves into the specialized principles and meticulous practices required to tame the electromagnetic behavior of circuits operating at these elevated frequencies. It bridges the gap between circuit theory and electromagnetic field theory, addressing the parasitic effects—unwanted capacitance, inductance, and radiation—that dominate performance. For engineers and designers, mastering these considerations is not merely an optimization step but a fundamental necessity to prevent a perfectly designed schematic from becoming a non-functional prototype, thereby ensuring signal fidelity, minimizing interference, and achieving the stringent performance targets demanded by modern high-speed applications.

Impedance Control and Transmission Line Theory

At the heart of RF layout design lies the imperative for controlled impedance. As signal wavelengths approach the physical dimensions of the PCB traces, these traces must be treated not as simple wires but as transmission lines. A transmission line is characterized by its per-unit-length inductance and capacitance, which together determine its characteristic impedance (typically 50 or 75 ohms). Maintaining a consistent impedance along the signal path from source to load is paramount to prevent signal reflections.

Reflections occur when there is an impedance discontinuity, causing portions of the signal to bounce back towards the source. This results in standing waves, signal distortion, and a severe degradation in power transfer. To avoid this, layout engineers meticulously calculate and design trace dimensions (width and thickness) relative to the PCB substrate's dielectric constant and height. This often involves using specific trace geometries like microstrip (a trace on an outer layer over a ground plane) or stripline (a trace embedded between two ground planes), each with its own equations and field confinement properties. Proper termination at the load, usually with a resistor matching the line's characteristic impedance, is essential to absorb the signal energy and eliminate reflections.

Grounding and Power Plane Strategies

Grounding in RF design is arguably more critical and complex than in digital or low-frequency analog design. An imperfect ground can introduce common-impedance coupling, ground loops, and act as an unintentional antenna. The primary goal is to provide a low-impedance return path for high-frequency currents, which requires a fundamentally different approach from the single-point grounding often used at lower frequencies.

A solid, unbroken ground plane is the gold standard in RF layouts. It serves as a universal reference plane, minimizes ground impedance, and provides shielding. For multilayer boards, dedicated ground layers are used. Vias must be placed frequently to stitch together ground planes on different layers, preventing them from resonating at certain frequencies. Similarly, power distribution requires careful planning. Power planes are often paired closely with adjacent ground planes to form a distributed decoupling capacitor, providing a low-impedance path for high-frequency noise. Strategic placement of multiple, small-value decoupling capacitors very close to IC power pins is crucial to suppress high-frequency transients and prevent noise from propagating through the power rail.

Component Selection, Placement, and Parasitics

Every physical component exhibits behavior beyond its ideal model at high frequencies. A simple wire, a resistor lead, or a capacitor's mounting pad introduces parasitic inductance and capacitance. These parasitics can cause a capacitor to become inductive above its self-resonant frequency or make a seemingly innocuous connection into a significant impedance. Therefore, component selection extends beyond nominal values to include package types (e.g., surface-mount devices, or SMDs, are vastly superior to through-hole parts), quality factors (Q), and self-resonant frequencies.

Placement is equally critical. The guiding principle is to minimize the length of all high-frequency current paths. This means placing critical components like amplifiers, filters, and oscillators as close together as possible. Long traces act as antennas and increase inductance. Sensitive nodes must be kept away from noisy ones. For instance, the output of a power amplifier should be physically isolated from the input of a low-noise amplifier to prevent oscillation or desensitization. Furthermore, component orientation can affect coupling; for example, adjacent inductors should be placed at right angles to minimize mutual magnetic coupling.

Shielding, Isolation, and Electromagnetic Compatibility (EMC)

At RF and microwave frequencies, circuits radiate and receive electromagnetic energy readily. Preventing unwanted emission (which can fail regulatory tests) and ensuring immunity from external interference are the dual goals of EMC. Layout is the first line of defense. Sensitive circuit blocks, such as local oscillators or low-noise input stages, are often isolated using shielding cans—metal enclosures soldered directly to the ground plane. These cans prevent radiative coupling between sections.

Isolation is also achieved through spatial separation and the use of guard rings—grounded traces that surround a sensitive trace or component to shunt away stray currents. Additionally, careful routing is essential: differential signaling can reject common-mode noise, and critical single-ended traces should be routed with adjacent ground traces (co-planar waveguide) for containment of fields. Filtering at every I/O connector, using ferrite beads and feedthrough capacitors, is standard practice to prevent noise from entering or leaving the board. A well-designed RF layout inherently considers the entire system as an electromagnetic entity, proactively managing fields rather than just currents.

Thermal Management and Material Selection

High-frequency circuits, particularly power amplifiers, generate significant heat. Excessive temperature degrades component performance, reduces reliability, and can cause thermal runaway. Effective thermal management must be integrated into the layout phase. This involves providing adequate thermal relief for heat-generating components, which often means connecting their thermal pads to large copper pours or internal ground planes using a grid of thermal vias. These vias conduct heat into the board's inner layers or to the opposite side where a heatsink can be attached.

The choice of PCB substrate material itself is a fundamental high-frequency consideration. Standard FR-4 material exhibits significant dielectric loss and poor consistency at frequencies above a few gigahertz. For microwave applications, specialized laminates with low dielectric loss (low loss tangent), stable dielectric constant over temperature and frequency, and tight manufacturing tolerances are used, such as Rogers, Teflon, or ceramic-filled materials. While more expensive, these materials ensure predictable performance, minimal signal attenuation, and stable impedance, which are non-negotiable for high-performance designs.

REPORT