-

Agriculture

Agriculture

-

Health-Care

Health-Care

-

Environment

Environment

-

Construction-Real-Estate

Construction-Real-Estate

-

Tools-Hardware

Tools-Hardware

-

Home-Garden

Home-Garden

-

Furniture

Furniture

-

Luggage-Bags-Cases

Luggage-Bags-Cases

-

Medical-devices-Supplies

Medical-devices-Supplies

-

Gifts-Crafts

Gifts-Crafts

-

Sports-Entertainment

Sports-Entertainment

-

Food-Beverage

Food-Beverage

-

Vehicles-Transportation

Vehicles-Transportation

-

Power-Transmission

Power-Transmission

-

Material-Handling

Material-Handling

-

Renewable-Energy

Renewable-Energy

-

Safety

Safety

-

Testing-Instrument-Equipment

Testing-Instrument-Equipment

-

Construction-Building-Machinery

Construction-Building-Machinery

-

Pet-Supplies

Pet-Supplies

-

Personal-Care-Household-Cleaning

Personal-Care-Household-Cleaning

-

Vehicle-Accessories-Electronics-Tools

Vehicle-Accessories-Electronics-Tools

-

School-Office-Supplies

School-Office-Supplies

-

Packaging-Printing

Packaging-Printing

-

Mother-Kids-Toys

Mother-Kids-Toys

-

Business-Services

Business-Services

-

Commercial-Equipment-Machinery

Commercial-Equipment-Machinery

-

Apparel-Accessories

Apparel-Accessories

-

Security

Security

-

Shoes-Accessories

Shoes-Accessories

-

Vehicle-Parts-Accessories

Vehicle-Parts-Accessories

-

Jewelry-Eyewear-Watches-Accessories

Jewelry-Eyewear-Watches-Accessories

-

Lights-Lighting

Lights-Lighting

-

Fabric-Textile-Raw-Material

Fabric-Textile-Raw-Material

-

Fabrication-Services

Fabrication-Services

-

Industrial-Machinery

Industrial-Machinery

-

Consumer-Electronics

Consumer-Electronics

-

Electrical-Equipment-Supplies

Electrical-Equipment-Supplies

-

Electronic-Components-Accessories-Telecommunications

Electronic-Components-Accessories-Telecommunications

-

Home-Appliances

Home-Appliances

-

Beauty

Beauty

-

Chemicals

Chemicals

-

Rubber-Plastics

Rubber-Plastics

-

Metals-Alloys

Metals-Alloys

- Masonry Materials

- Curtain Walls & Accessories

- Earthwork Products

- Fireproofing Materials

- Heat Insulation Materials

- Plastic Building Materials

- Building Boards

- Soundproofing Materials

- Timber

- Waterproofing Materials

- Balustrades & Handrails

- Bathroom & Kitchen

- Flooring & Accessories

- Tiles & Accessories

- Door, Window & Accessories

- Fireplaces & Stoves

- Floor Heating Systems & Parts

- Stairs & Stair Parts

- Ceilings

- Elevators & Escalators

- Stone

- Countertops, Vanity Tops & Table Tops

- Mosaics

- Metal Building Materials

- Multifunctional Materials

- Ladders & Scaffoldings

- Mouldings

- Corner Guards

- Decorative Films

- Formwork

- Building & Industrial Glass

- Other Construction & Real Estate

- Wallpapers/Wall panels

- HVAC System & Parts

- Outdoor Facilities

- Prefabricated Buildings

- Festive & Party Supplies

- Bathroom Products

- Household Sundries

- Rain Gear

- Garden Supplies

- Household Cleaning Tools & Accessories

- Lighters & Smoking Accessories

- Home Storage & Organization

- Household Scales

- Smart Home Improvement

- Home Textiles

- Kitchenware

- Drinkware & Accessories

- Dinnerware, Coffee & Wine

- Home Decor

- Golf

- Fitness & Body Building

- Amusement Park Facilities

- Billiards, Board Game,Coin Operated Games

- Musical Instruments

- Outdoor Affordable Luxury Sports

- Camping & Hiking

- Fishing

- Sports Safety&Rehabilitation

- Ball Sports Equipments

- Water Sports

- Winter Sports

- Luxury Travel Equipments

- Sports Shoes, Bags & Accessories

- Cycling

- Other Sports & Entertainment Products

- Artificial Grass&Sports Flooring&Sports Court Equipment

- Scooters

- Food Ingredients

- Honey & Honey Products

- Snacks

- Nuts & Kernels

- Seafood

- Plant & Animal Oil

- Beverages

- Fruit & Vegetable Products

- Frog & Escargot

- Bean Products

- Egg Products

- Dairy Products

- Seasonings & Condiments

- Canned Food

- Instant Food

- Baked Goods

- Other Food & Beverage

- Meat & Poultry

- Confectionery

- Grain Products

- Feminie Care

- Hair Care & Styling

- Body Care

- Hands & Feet Care

- Hygiene Products

- Men's Grooming

- Laundry Cleaning Supplies

- Travel Size & Gift Sets

- Room Deodorizers

- Other Personal Care Products

- Pest Control Products

- Special Household Cleaning

- Floor Cleaning

- Kitchen & Bathroom Cleaning

- Oral Care

- Bath Supplies

- Yellow Pages

- Correction Supplies

- Office Binding Supplies

- Office Cutting Supplies

- Board Erasers

- Office Adhesives & Tapes

- Education Supplies

- Pencil Cases & Bags

- Notebooks & Writing Pads

- File Folder Accessories

- Calendars

- Writing Accessories

- Commercial Office Supplies

- Pencil Sharpeners

- Pens

- Letter Pad/Paper

- Paper Envelopes

- Desk Organizers

- Pencils

- Markers & Highlighters

- Filing Products

- Art Supplies

- Easels

- Badge Holder & Accessories

- Office Paper

- Printer Supplies

- Book Covers

- Other Office & School Supplies

- Stationery Set

- Boards

- Clipboards

- Stamps

- Drafting Supplies

- Stencils

- Electronic Dictionary

- Books

- Map

- Magazines

- Calculators

- Baby & Toddler Toys

- Educational Toys

- Classic Toys

- Dress Up & Pretend Play

- Toy Vehicle

- Stuffed Animals & Plush Toys

- Outdoor Toys & Structures

- Balloons & Accessories

- Baby Food

- Children's Clothing

- Baby Supplies & Products

- Maternity Clothes

- Kids Shoes

- Baby Care

- Novelty & Gag Toys

- Dolls & Accessories

- Puzzle & Games

- Blocks & Model Building Toys

- Toddler Clothing

- Baby Clothing

- Kids' Luggage & Bags

- Arts, Crafts & DIY Toys

- Action & Toy Figures

- Baby Appliances

- Hobbies & Models

- Remote Control Toys

- Promotional Toys

- Pregnancy & Maternity

- Hygiene Products

- Kid's Textile&Bedding

- Novelty & Special Use

- Toy Weapons

- Baby Gifts

- Baby Storage & Organization

- Auto Drive Systems

- ATV/UTV Parts & Accessories

- Marine Parts & Accessories

- Other Auto Parts

- Trailer Parts & Accessories

- Auto Transmission Systems

- Train Parts & Accessories

- Universal Parts

- Railway Parts & Accessories

- Auto Brake Systems

- Aviation Parts & Accessories

- Truck Parts & Accessories

- Auto Suspension Systems

- Auto Lighting Systems

- New Energy Vehicle Parts & Accessories

- Auto Steering Systems

- Wheels, Tires & Accessories

- Bus Parts & Accessories

- Auto Performance Parts

- Cooling System

- Go-Kart & Kart Racer Parts & Accessories

- Air Conditioning Systems

- Heavy Duty Vehicle Parts & Accessories

- Auto Electrical Systems

- Auto Body Systems

- Auto Engine Systems

- Container Parts & Accessories

- Motorcycle Parts & Accessories

- Refrigeration & Heat Exchange Equipment

- Machine Tool Equipment

- Food & Beverage Machinery

- Agricultural Machinery & Equipment

- Apparel & Textile Machinery

- Chemical Machinery

- Packaging Machines

- Paper Production Machinery

- Plastic & Rubber Processing Machinery

- Industrial Robots

- Electronic Products Machinery

- Metal & Metallurgy Machinery

- Woodworking Machinery

- Home Product Manufacturing Machinery

- Machinery Accessories

- Environmental Machinery

- Machinery Service

- Electrical Equipment Manufacturing Machinery

- Industrial Compressors & Parts

- Tobacco & Cigarette Machinery

- Production Line

- Used Industrial Machinery

- Electronics Production Machinery

- Other Machinery & Industrial Equipment

- Camera, Photo & Accessories

- Portable Audio, Video & Accessories

- Television, Home Audio, Video & Accessories

- Video Games & Accessories

- Mobile Phone & Accessories

- Electronic Publications

- Earphone & Headphone & Accessories

- Speakers & Accessories

- Smart Electronics

- TV Receivers & Accessories

- Mobile Phone & Computer Repair Parts

- Chargers, Batteries & Power Supplies

- Used Electronics

- VR, AR, MR Hardware & Software

- Projectors & Presentation Equipments

- Other Consumer Electronics

- Cables & Commonly Used Accessories

- Computer Hardware & Software

- Displays, Signage and Optoelectronics

- Discrete Semiconductors

- Wireless & IoT Module and Products

- Telecommunications

- Connectors, Terminals & Accessories

- Development Boards, Electronic Modules and Kits

- Circuit Protection

- Sensors

- Isolators

- Audio Components and Products

- Integrated Circuits

- Power Supplies

- Relays

- RF, Microwave and RFID

- Electronic Accessories & Supplies

- Passive Components

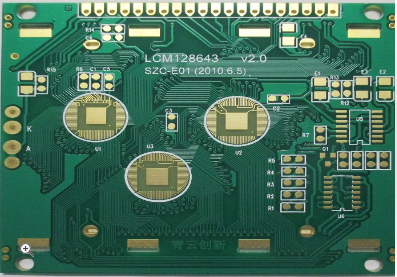

- PCB & PCBA

- Air Quality Appliances

- Home Appliance Parts

- Heating & Cooling Appliances

- Small Kitchen Appliances

- Laundry Appliances

- Water Heaters

- Water Treatment Appliances

- Refrigerators & Freezers

- Personal Care & Beauty Appliances

- Major Kitchen Appliances

- Cleaning Appliances

- Second-hand Appliances

- Smart Home Appliances

- Other Home Appliances

- Energy Chemicals

- Inorganic Chemicals

- Basic Organic Chemicals

- Agrochemicals

- Admixture & Additives

- Catalysts & Chemical Auxiliary Agents

- Pigments & Dyestuff

- Coating & Paint

- Daily Chemicals

- Polymer

- Organic Intermediate

- Adhesives & Sealants

- Chemical Waste

- Biological Chemical Products

- Surface Treatment Chemicals

- Painting & Coating

- Chemical Reagents

- Flavor & Fragrance

- Non-Explosive Demolition Agents

- Other Chemicals

- Custom Chemical Services

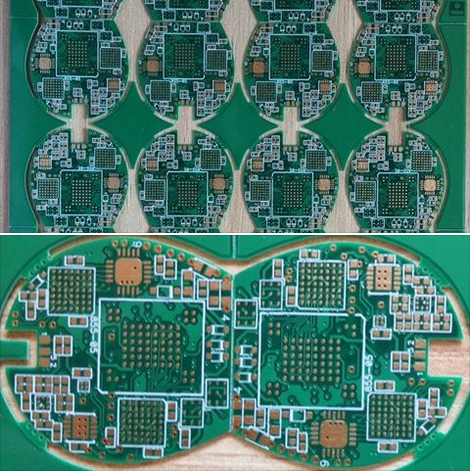

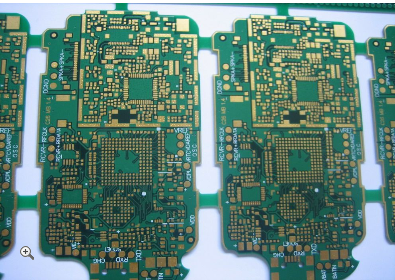

Mastering Multilayer PCB Stackup Design For Enhanced Electronic Performance

In the relentless pursuit of miniaturization, higher speeds, and greater functionality in modern electronics, the printed circuit board (PCB) has evolved far beyond a simple platform for component interconnection. At the heart of today's sophisticated devices lies the multilayer PCB, a complex laminate structure whose internal architecture—the stackup—is a critical determinant of overall system performance. Mastering multilayer PCB stackup design is no longer a secondary consideration but a foundational engineering discipline essential for achieving signal integrity, power integrity, electromagnetic compatibility (EMC), and thermal management. This article delves into the core principles and strategic considerations involved in crafting an optimal PCB stackup, moving beyond basic layer count to explore how deliberate material selection and layer ordering can dramatically enhance electronic performance, reliability, and manufacturability.

The Strategic Foundation: Defining Stackup Objectives and Constraints

Before a single layer is drawn, a successful stackup design begins with a clear understanding of the project's objectives and constraints. This phase involves defining the electrical, mechanical, and economic parameters that will guide all subsequent decisions. Key questions must be answered: What are the operating frequencies and data rates? What is the target impedance for critical signals? What are the power requirements and noise margins? Furthermore, mechanical constraints such as the final board thickness, the number of layers feasible within the budget, and the chosen fabrication capabilities of the PCB manufacturer must be established.

This initial planning sets the stage for all other stackup decisions. For instance, a high-speed digital design prioritizing signal integrity will have vastly different requirements than a dense, mixed-signal board containing sensitive analog circuits and RF components. Similarly, a design for a cost-sensitive consumer product may prioritize a minimal layer count, while a high-reliability aerospace application may emphasize robust power distribution and thermal dissipation, even at higher cost. By meticulously defining these goals upfront, designers can create a stackup that is not just functionally adequate but optimally tuned for its specific application.

Architecting for Signal Integrity: Controlled Impedance and Return Paths

Perhaps the most crucial role of the stackup is in preserving signal integrity, especially for high-speed digital and high-frequency analog circuits. A poorly designed stackup can lead to signal degradation, crosstalk, and timing errors that render a system unstable. The primary tools for managing signal integrity in the stackup are controlled impedance and the provision of clear, uninterrupted return paths for signals.

Controlled impedance is achieved by precisely designing the physical dimensions of a trace—its width and thickness—in relation to the dielectric material surrounding it and the distance to its reference plane (typically a ground or power plane). The stackup defines these dielectric heights (core and prepreg thicknesses) and the copper weights. Designers use these parameters in impedance calculators to determine trace geometries that match the required impedance (e.g., 50Ω or 100Ω differential). Consistency in these dielectric layers across the board is paramount for uniform impedance.

Equally important is the management of return currents. High-frequency signal currents return to their source via the path of least inductance, which is directly underneath the signal trace on an adjacent reference plane. A well-designed stackup ensures that every critical signal layer is adjacent to a solid reference plane. Breaking this plane with large splits or gaps forces the return current to find a longer, more inductive path, creating large current loops that radiate noise and increase susceptibility. Therefore, strategic pairing of signal and plane layers is a non-negotiable principle for maintaining clean signals and reducing electromagnetic emissions.

Powering the System: Robust Power Distribution Network (PDN) Design

The stackup is the physical embodiment of the Power Distribution Network (PDN). Its design directly impacts power integrity, which governs the stability of the voltage supplied to active components. A weak PDN, manifested as excessive impedance or noise on the power rails, can cause logic errors, reduced noise margins, and even component malfunction.

A fundamental strategy in stackup design is the use of dedicated power and ground plane pairs. Placing these planes closely together forms a natural, high-frequency decoupling capacitor due to the parallel plate capacitance between them. This inherent capacitance helps suppress high-frequency noise on the power rail, supplementing discrete decoupling capacitors. The stackup should be arranged to create multiple such plane pairs for different voltage levels, ensuring low-impedance power delivery across a broad frequency range.

Furthermore, the sequence of layers plays a role. Placing critical power planes adjacent to ground planes, and sandwiching high-speed signal layers between them, creates a shielded, stripline configuration. This not only contains the fields from the signals but also provides a stable reference for both the signals and the power. The strategic assignment of voltage layers and their proximity to ground directly influences the board's ability to deliver clean, stable power, especially during moments of high current demand when chips switch simultaneously.

Containing and Mitigating Electromagnetic Interference (EMI)

Electromagnetic Compatibility (EMC)—the ability of a device to function without causing or being susceptible to interference—is heavily dictated by PCB stackup design. The stackup is the first line of defense against both emitted radiation and external susceptibility. A thoughtful layer arrangement can act as a built-in shielding strategy.

The use of solid, unbroken ground planes is the most effective EMI control feature in a stackup. These planes provide shielding between signal layers, contain electromagnetic fields, and offer a low-impedance path for return currents, minimizing loop areas. As a rule, external signal layers should always be placed adjacent to a ground plane. If sensitive or high-speed traces must be on an outer layer, placing a ground plane directly underneath them is essential to contain their fields and reduce radiation.

For very noise-sensitive designs or those with stringent emission limits, a symmetric stackup around the board's centerline can be highly beneficial. Symmetry balances the inherent stresses in the laminated board, improving manufacturability and reducing the risk of warping. From an EMC perspective, a symmetric stackup with ground planes near the outer surfaces can create a "Faraday cage" effect, helping to contain internal noise. By carefully considering the placement of noisy and quiet circuit sections across layers and using planes as shields, designers can proactively mitigate EMI challenges long before a board is tested in an EMC chamber.

Material Selection and Fabrication Considerations

The performance of a brilliantly architected stackup can be undermined by inappropriate material choices. The dielectric materials, or laminates, used between copper layers have electrical and mechanical properties that directly impact performance. The key parameter is the dielectric constant (Dk or εr), which affects signal propagation speed and impedance. For consistent high-speed performance, a material with a stable Dk across frequency and temperature is critical. Loss tangent (Df) is another vital property, indicating how much signal energy is dissipated as heat; lower loss materials are essential for very high-frequency or long-distance transmission lines.

Beyond electrical properties, thermal and mechanical characteristics must align with the application. The Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) and Thermal Decomposition Temperature (Td) indicate a material's ability to withstand the heat of assembly (like lead-free soldering) and operation. Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE) matching is crucial for reliability, especially when using large Ball Grid Array (BGA) components, to prevent solder joint failure over temperature cycles.

Finally, the stackup design must be translated into a manufacturable product. Close collaboration with the PCB fabricator during the stackup planning phase is invaluable. They can provide guidance on standard material thicknesses, available copper weights, and processing capabilities (like minimum dielectric spacing). Providing a complete stackup specification—including all material types, final thickness targets, and impedance requirements—ensures the fabricated board will match the design intent, turning a theoretical stackup into a high-performance reality.

REPORT