-

Agriculture

Agriculture

-

Health-Care

Health-Care

-

Environment

Environment

-

Construction-Real-Estate

Construction-Real-Estate

-

Tools-Hardware

Tools-Hardware

-

Home-Garden

Home-Garden

-

Furniture

Furniture

-

Luggage-Bags-Cases

Luggage-Bags-Cases

-

Medical-devices-Supplies

Medical-devices-Supplies

-

Gifts-Crafts

Gifts-Crafts

-

Sports-Entertainment

Sports-Entertainment

-

Food-Beverage

Food-Beverage

-

Vehicles-Transportation

Vehicles-Transportation

-

Power-Transmission

Power-Transmission

-

Material-Handling

Material-Handling

-

Renewable-Energy

Renewable-Energy

-

Safety

Safety

-

Testing-Instrument-Equipment

Testing-Instrument-Equipment

-

Construction-Building-Machinery

Construction-Building-Machinery

-

Pet-Supplies

Pet-Supplies

-

Personal-Care-Household-Cleaning

Personal-Care-Household-Cleaning

-

Vehicle-Accessories-Electronics-Tools

Vehicle-Accessories-Electronics-Tools

-

School-Office-Supplies

School-Office-Supplies

-

Packaging-Printing

Packaging-Printing

-

Mother-Kids-Toys

Mother-Kids-Toys

-

Business-Services

Business-Services

-

Commercial-Equipment-Machinery

Commercial-Equipment-Machinery

-

Apparel-Accessories

Apparel-Accessories

-

Security

Security

-

Shoes-Accessories

Shoes-Accessories

-

Vehicle-Parts-Accessories

Vehicle-Parts-Accessories

-

Jewelry-Eyewear-Watches-Accessories

Jewelry-Eyewear-Watches-Accessories

-

Lights-Lighting

Lights-Lighting

-

Fabric-Textile-Raw-Material

Fabric-Textile-Raw-Material

-

Fabrication-Services

Fabrication-Services

-

Industrial-Machinery

Industrial-Machinery

-

Consumer-Electronics

Consumer-Electronics

-

Electrical-Equipment-Supplies

Electrical-Equipment-Supplies

-

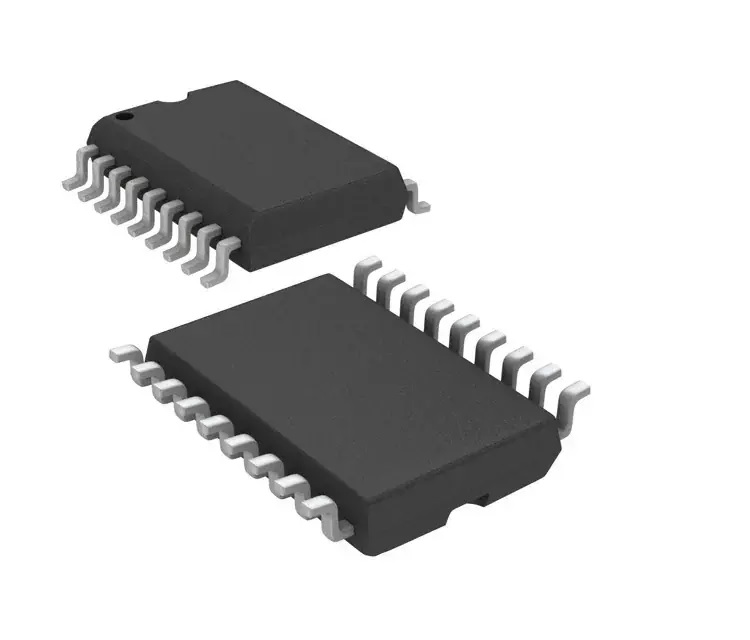

Electronic-Components-Accessories-Telecommunications

Electronic-Components-Accessories-Telecommunications

-

Home-Appliances

Home-Appliances

-

Beauty

Beauty

-

Chemicals

Chemicals

-

Rubber-Plastics

Rubber-Plastics

-

Metals-Alloys

Metals-Alloys

- Masonry Materials

- Curtain Walls & Accessories

- Earthwork Products

- Fireproofing Materials

- Heat Insulation Materials

- Plastic Building Materials

- Building Boards

- Soundproofing Materials

- Timber

- Waterproofing Materials

- Balustrades & Handrails

- Bathroom & Kitchen

- Flooring & Accessories

- Tiles & Accessories

- Door, Window & Accessories

- Fireplaces & Stoves

- Floor Heating Systems & Parts

- Stairs & Stair Parts

- Ceilings

- Elevators & Escalators

- Stone

- Countertops, Vanity Tops & Table Tops

- Mosaics

- Metal Building Materials

- Multifunctional Materials

- Ladders & Scaffoldings

- Mouldings

- Corner Guards

- Decorative Films

- Formwork

- Building & Industrial Glass

- Other Construction & Real Estate

- Wallpapers/Wall panels

- HVAC System & Parts

- Outdoor Facilities

- Prefabricated Buildings

- Festive & Party Supplies

- Bathroom Products

- Household Sundries

- Rain Gear

- Garden Supplies

- Household Cleaning Tools & Accessories

- Lighters & Smoking Accessories

- Home Storage & Organization

- Household Scales

- Smart Home Improvement

- Home Textiles

- Kitchenware

- Drinkware & Accessories

- Dinnerware, Coffee & Wine

- Home Decor

- Golf

- Fitness & Body Building

- Amusement Park Facilities

- Billiards, Board Game,Coin Operated Games

- Musical Instruments

- Outdoor Affordable Luxury Sports

- Camping & Hiking

- Fishing

- Sports Safety&Rehabilitation

- Ball Sports Equipments

- Water Sports

- Winter Sports

- Luxury Travel Equipments

- Sports Shoes, Bags & Accessories

- Cycling

- Other Sports & Entertainment Products

- Artificial Grass&Sports Flooring&Sports Court Equipment

- Scooters

- Food Ingredients

- Honey & Honey Products

- Snacks

- Nuts & Kernels

- Seafood

- Plant & Animal Oil

- Beverages

- Fruit & Vegetable Products

- Frog & Escargot

- Bean Products

- Egg Products

- Dairy Products

- Seasonings & Condiments

- Canned Food

- Instant Food

- Baked Goods

- Other Food & Beverage

- Meat & Poultry

- Confectionery

- Grain Products

- Feminie Care

- Hair Care & Styling

- Body Care

- Hands & Feet Care

- Hygiene Products

- Men's Grooming

- Laundry Cleaning Supplies

- Travel Size & Gift Sets

- Room Deodorizers

- Other Personal Care Products

- Pest Control Products

- Special Household Cleaning

- Floor Cleaning

- Kitchen & Bathroom Cleaning

- Oral Care

- Bath Supplies

- Yellow Pages

- Correction Supplies

- Office Binding Supplies

- Office Cutting Supplies

- Board Erasers

- Office Adhesives & Tapes

- Education Supplies

- Pencil Cases & Bags

- Notebooks & Writing Pads

- File Folder Accessories

- Calendars

- Writing Accessories

- Commercial Office Supplies

- Pencil Sharpeners

- Pens

- Letter Pad/Paper

- Paper Envelopes

- Desk Organizers

- Pencils

- Markers & Highlighters

- Filing Products

- Art Supplies

- Easels

- Badge Holder & Accessories

- Office Paper

- Printer Supplies

- Book Covers

- Other Office & School Supplies

- Stationery Set

- Boards

- Clipboards

- Stamps

- Drafting Supplies

- Stencils

- Electronic Dictionary

- Books

- Map

- Magazines

- Calculators

- Baby & Toddler Toys

- Educational Toys

- Classic Toys

- Dress Up & Pretend Play

- Toy Vehicle

- Stuffed Animals & Plush Toys

- Outdoor Toys & Structures

- Balloons & Accessories

- Baby Food

- Children's Clothing

- Baby Supplies & Products

- Maternity Clothes

- Kids Shoes

- Baby Care

- Novelty & Gag Toys

- Dolls & Accessories

- Puzzle & Games

- Blocks & Model Building Toys

- Toddler Clothing

- Baby Clothing

- Kids' Luggage & Bags

- Arts, Crafts & DIY Toys

- Action & Toy Figures

- Baby Appliances

- Hobbies & Models

- Remote Control Toys

- Promotional Toys

- Pregnancy & Maternity

- Hygiene Products

- Kid's Textile&Bedding

- Novelty & Special Use

- Toy Weapons

- Baby Gifts

- Baby Storage & Organization

- Auto Drive Systems

- ATV/UTV Parts & Accessories

- Marine Parts & Accessories

- Other Auto Parts

- Trailer Parts & Accessories

- Auto Transmission Systems

- Train Parts & Accessories

- Universal Parts

- Railway Parts & Accessories

- Auto Brake Systems

- Aviation Parts & Accessories

- Truck Parts & Accessories

- Auto Suspension Systems

- Auto Lighting Systems

- New Energy Vehicle Parts & Accessories

- Auto Steering Systems

- Wheels, Tires & Accessories

- Bus Parts & Accessories

- Auto Performance Parts

- Cooling System

- Go-Kart & Kart Racer Parts & Accessories

- Air Conditioning Systems

- Heavy Duty Vehicle Parts & Accessories

- Auto Electrical Systems

- Auto Body Systems

- Auto Engine Systems

- Container Parts & Accessories

- Motorcycle Parts & Accessories

- Refrigeration & Heat Exchange Equipment

- Machine Tool Equipment

- Food & Beverage Machinery

- Agricultural Machinery & Equipment

- Apparel & Textile Machinery

- Chemical Machinery

- Packaging Machines

- Paper Production Machinery

- Plastic & Rubber Processing Machinery

- Industrial Robots

- Electronic Products Machinery

- Metal & Metallurgy Machinery

- Woodworking Machinery

- Home Product Manufacturing Machinery

- Machinery Accessories

- Environmental Machinery

- Machinery Service

- Electrical Equipment Manufacturing Machinery

- Industrial Compressors & Parts

- Tobacco & Cigarette Machinery

- Production Line

- Used Industrial Machinery

- Electronics Production Machinery

- Other Machinery & Industrial Equipment

- Camera, Photo & Accessories

- Portable Audio, Video & Accessories

- Television, Home Audio, Video & Accessories

- Video Games & Accessories

- Mobile Phone & Accessories

- Electronic Publications

- Earphone & Headphone & Accessories

- Speakers & Accessories

- Smart Electronics

- TV Receivers & Accessories

- Mobile Phone & Computer Repair Parts

- Chargers, Batteries & Power Supplies

- Used Electronics

- VR, AR, MR Hardware & Software

- Projectors & Presentation Equipments

- Other Consumer Electronics

- Cables & Commonly Used Accessories

- Computer Hardware & Software

- Displays, Signage and Optoelectronics

- Discrete Semiconductors

- Wireless & IoT Module and Products

- Telecommunications

- Connectors, Terminals & Accessories

- Development Boards, Electronic Modules and Kits

- Circuit Protection

- Sensors

- Isolators

- Audio Components and Products

- Integrated Circuits

- Power Supplies

- Relays

- RF, Microwave and RFID

- Electronic Accessories & Supplies

- Passive Components

- PCB & PCBA

- Air Quality Appliances

- Home Appliance Parts

- Heating & Cooling Appliances

- Small Kitchen Appliances

- Laundry Appliances

- Water Heaters

- Water Treatment Appliances

- Refrigerators & Freezers

- Personal Care & Beauty Appliances

- Major Kitchen Appliances

- Cleaning Appliances

- Second-hand Appliances

- Smart Home Appliances

- Other Home Appliances

- Energy Chemicals

- Inorganic Chemicals

- Basic Organic Chemicals

- Agrochemicals

- Admixture & Additives

- Catalysts & Chemical Auxiliary Agents

- Pigments & Dyestuff

- Coating & Paint

- Daily Chemicals

- Polymer

- Organic Intermediate

- Adhesives & Sealants

- Chemical Waste

- Biological Chemical Products

- Surface Treatment Chemicals

- Painting & Coating

- Chemical Reagents

- Flavor & Fragrance

- Non-Explosive Demolition Agents

- Other Chemicals

- Custom Chemical Services

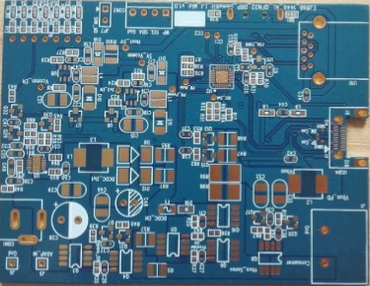

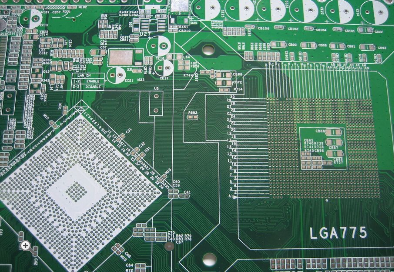

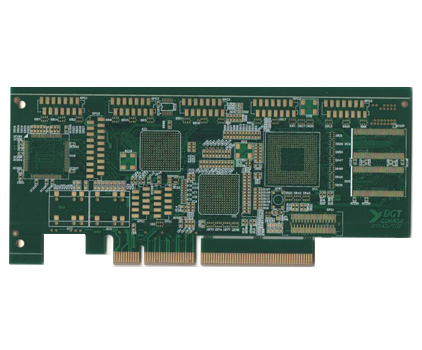

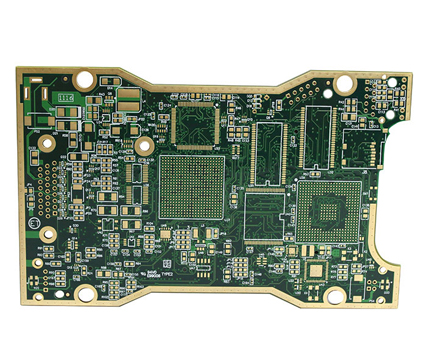

Optimizing PCB Impedance for Enhanced Signal Transmission Techniques to Minimize Loss and Ensure Reliable Circuit Board Functionality

In the rapidly evolving landscape of modern electronics, the demand for higher data rates, greater bandwidth, and enhanced reliability has never been more critical. At the heart of this technological advancement lies the printed circuit board (PCB), the fundamental platform that interconnects components and facilitates signal communication. As signal frequencies soar into the gigahertz range, the integrity of these signals becomes paramount. Signal degradation, manifested as distortion, reflection, or loss, can severely compromise the performance of devices ranging from smartphones and laptops to advanced telecommunications infrastructure and medical equipment. This underscores the vital importance of optimizing PCB impedance—a core electrical characteristic that, when meticulously controlled, ensures efficient signal transmission, minimizes energy loss, and guarantees the reliable functionality of the entire circuit board system. Mastering impedance optimization is not merely a technical detail but a foundational requirement for designing robust, high-performance electronic systems in today's digital age.

The Fundamentals of Controlled Impedance and Signal Integrity

Impedance, in the context of a PCB trace, is the measure of opposition that the trace presents to the alternating current (AC) of a high-speed signal. It is a complex quantity encompassing both resistance and reactance. For optimal signal transmission, the impedance of the trace must match the impedance of the source driver and the destination receiver, a condition known as impedance matching. When impedances are mismatched, a portion of the signal reflects back towards the source. These reflections interfere with the original signal, causing ringing, overshoot, and undershoot, which distort the signal waveform and can lead to data errors.

Controlled impedance design, therefore, is the practice of engineering PCB traces to maintain a specific, consistent impedance value throughout their length. The most common target is the characteristic impedance, typically 50 ohms for single-ended signals or 100 ohms for differential pairs in many applications. Achieving this requires precise control over several physical and material parameters of the PCB stack-up. The primary formula governing the characteristic impedance of a microstrip trace (on an outer layer) involves the trace width, the thickness of the dielectric material beneath it, and the dielectric constant (Dk or εr) of that material. For stripline traces (embedded between two reference planes), the distance to both planes is critical. Understanding and manipulating these relationships is the first step in mitigating signal loss and ensuring that digital pulses arrive intact and unambiguous at their destination.

Key Design Parameters and Material Selection

The journey to optimized impedance begins with intelligent material selection and stack-up design. The dielectric constant (Dk) of the PCB substrate material is a primary factor. Materials with a low and stable Dk across the desired frequency range, such as Rogers or specialized FR-4 blends, are preferred for high-speed designs as they reduce signal propagation delay and loss. The dissipation factor (Df), which indicates the material's inherent signal loss, is equally crucial; a lower Df translates to less energy converted to heat within the dielectric.

Beyond the material itself, the physical geometry dictated by the stack-up is engineered with precision. The trace width and thickness are directly adjustable parameters. A wider trace lowers impedance, while a narrower one increases it. The thickness of the copper (ounce weight) also plays a role. The dielectric height—the distance between the signal trace and its adjacent reference plane (ground or power)—is perhaps the most sensitive variable. A smaller height increases capacitance, thereby lowering impedance. Modern PCB design software incorporates sophisticated field solvers that allow engineers to simulate and adjust these parameters interactively to hit the target impedance before the board is ever manufactured, accounting for the final plating and etching processes that will slightly alter the as-designed dimensions.

Advanced Routing Techniques and Topology Management

Once the stack-up is defined, the implementation of routing strategies becomes critical. For differential pairs, which are essential for high-speed interfaces like USB, PCIe, and DDR memory, maintaining consistent spacing (coupling) between the two traces is as important as controlling the impedance of each individual trace. Variations in spacing alter the differential impedance and can introduce common-mode noise. Length matching is another non-negotiable practice; signals traveling on parallel paths must arrive simultaneously to avoid skew. This is often achieved by adding gentle serpentine tuning sections to the shorter trace, avoiding sharp right-angle bends which cause impedance discontinuities and increase radiation.

Furthermore, the management of vias—the vertical connections between layers—is a major focus area. A via is inherently a discontinuity in the transmission line, presenting a stub and a change in geometry that can cause significant reflection and loss, especially at high frequencies. Techniques to mitigate via impact include using back-drilling to remove unused via stubs, employing via-in-pad designs, and ensuring each signal via has a nearby return via to provide a continuous reference plane path for the return current. The topology of the entire network, whether it's a point-to-point link or a multi-drop bus, must be considered from the outset, as each topology presents unique challenges for maintaining a clean impedance profile from end to end.

Manufacturing Tolerances and Validation through Testing

Even the most meticulous design can be undermined by manufacturing variations. The etching process can cause trace widths to deviate from the design file. The dielectric material's thickness and Dk can have production tolerances. The plating of vias and through-holes may not be perfectly uniform. These real-world tolerances must be accounted for during the design phase by specifying acceptable impedance variation windows (e.g., 50Ω ±10%) and by collaborating closely with the PCB fabricator. Providing them with clear impedance control requirements allows them to adjust their processes, often by creating test coupons on the panel that are used to fine-tune the production run.

Verification is the final, essential step. This is achieved through rigorous testing, primarily using a Time Domain Reflectometer (TDR). A TDR sends a fast step signal down a trace and measures the reflections. By analyzing the reflected waveform, engineers can precisely measure the actual impedance of the fabricated trace, locate any discontinuities (like a bad via or a neck-down section), and confirm that it stays within the specified tolerance band along its entire length. This empirical data closes the loop, validating the design and manufacturing process and ensuring that the physical board performs as the simulations predicted, thereby guaranteeing reliable circuit functionality in the end product.

REPORT