-

Agriculture

Agriculture

-

Health-Care

Health-Care

-

Environment

Environment

-

Construction-Real-Estate

Construction-Real-Estate

-

Tools-Hardware

Tools-Hardware

-

Home-Garden

Home-Garden

-

Furniture

Furniture

-

Luggage-Bags-Cases

Luggage-Bags-Cases

-

Medical-devices-Supplies

Medical-devices-Supplies

-

Gifts-Crafts

Gifts-Crafts

-

Sports-Entertainment

Sports-Entertainment

-

Food-Beverage

Food-Beverage

-

Vehicles-Transportation

Vehicles-Transportation

-

Power-Transmission

Power-Transmission

-

Material-Handling

Material-Handling

-

Renewable-Energy

Renewable-Energy

-

Safety

Safety

-

Testing-Instrument-Equipment

Testing-Instrument-Equipment

-

Construction-Building-Machinery

Construction-Building-Machinery

-

Pet-Supplies

Pet-Supplies

-

Personal-Care-Household-Cleaning

Personal-Care-Household-Cleaning

-

Vehicle-Accessories-Electronics-Tools

Vehicle-Accessories-Electronics-Tools

-

School-Office-Supplies

School-Office-Supplies

-

Packaging-Printing

Packaging-Printing

-

Mother-Kids-Toys

Mother-Kids-Toys

-

Business-Services

Business-Services

-

Commercial-Equipment-Machinery

Commercial-Equipment-Machinery

-

Apparel-Accessories

Apparel-Accessories

-

Security

Security

-

Shoes-Accessories

Shoes-Accessories

-

Vehicle-Parts-Accessories

Vehicle-Parts-Accessories

-

Jewelry-Eyewear-Watches-Accessories

Jewelry-Eyewear-Watches-Accessories

-

Lights-Lighting

Lights-Lighting

-

Fabric-Textile-Raw-Material

Fabric-Textile-Raw-Material

-

Fabrication-Services

Fabrication-Services

-

Industrial-Machinery

Industrial-Machinery

-

Consumer-Electronics

Consumer-Electronics

-

Electrical-Equipment-Supplies

Electrical-Equipment-Supplies

-

Electronic-Components-Accessories-Telecommunications

Electronic-Components-Accessories-Telecommunications

-

Home-Appliances

Home-Appliances

-

Beauty

Beauty

-

Chemicals

Chemicals

-

Rubber-Plastics

Rubber-Plastics

-

Metals-Alloys

Metals-Alloys

- Masonry Materials

- Curtain Walls & Accessories

- Earthwork Products

- Fireproofing Materials

- Heat Insulation Materials

- Plastic Building Materials

- Building Boards

- Soundproofing Materials

- Timber

- Waterproofing Materials

- Balustrades & Handrails

- Bathroom & Kitchen

- Flooring & Accessories

- Tiles & Accessories

- Door, Window & Accessories

- Fireplaces & Stoves

- Floor Heating Systems & Parts

- Stairs & Stair Parts

- Ceilings

- Elevators & Escalators

- Stone

- Countertops, Vanity Tops & Table Tops

- Mosaics

- Metal Building Materials

- Multifunctional Materials

- Ladders & Scaffoldings

- Mouldings

- Corner Guards

- Decorative Films

- Formwork

- Building & Industrial Glass

- Other Construction & Real Estate

- Wallpapers/Wall panels

- HVAC System & Parts

- Outdoor Facilities

- Prefabricated Buildings

- Festive & Party Supplies

- Bathroom Products

- Household Sundries

- Rain Gear

- Garden Supplies

- Household Cleaning Tools & Accessories

- Lighters & Smoking Accessories

- Home Storage & Organization

- Household Scales

- Smart Home Improvement

- Home Textiles

- Kitchenware

- Drinkware & Accessories

- Dinnerware, Coffee & Wine

- Home Decor

- Golf

- Fitness & Body Building

- Amusement Park Facilities

- Billiards, Board Game,Coin Operated Games

- Musical Instruments

- Outdoor Affordable Luxury Sports

- Camping & Hiking

- Fishing

- Sports Safety&Rehabilitation

- Ball Sports Equipments

- Water Sports

- Winter Sports

- Luxury Travel Equipments

- Sports Shoes, Bags & Accessories

- Cycling

- Other Sports & Entertainment Products

- Artificial Grass&Sports Flooring&Sports Court Equipment

- Scooters

- Food Ingredients

- Honey & Honey Products

- Snacks

- Nuts & Kernels

- Seafood

- Plant & Animal Oil

- Beverages

- Fruit & Vegetable Products

- Frog & Escargot

- Bean Products

- Egg Products

- Dairy Products

- Seasonings & Condiments

- Canned Food

- Instant Food

- Baked Goods

- Other Food & Beverage

- Meat & Poultry

- Confectionery

- Grain Products

- Feminie Care

- Hair Care & Styling

- Body Care

- Hands & Feet Care

- Hygiene Products

- Men's Grooming

- Laundry Cleaning Supplies

- Travel Size & Gift Sets

- Room Deodorizers

- Other Personal Care Products

- Pest Control Products

- Special Household Cleaning

- Floor Cleaning

- Kitchen & Bathroom Cleaning

- Oral Care

- Bath Supplies

- Yellow Pages

- Correction Supplies

- Office Binding Supplies

- Office Cutting Supplies

- Board Erasers

- Office Adhesives & Tapes

- Education Supplies

- Pencil Cases & Bags

- Notebooks & Writing Pads

- File Folder Accessories

- Calendars

- Writing Accessories

- Commercial Office Supplies

- Pencil Sharpeners

- Pens

- Letter Pad/Paper

- Paper Envelopes

- Desk Organizers

- Pencils

- Markers & Highlighters

- Filing Products

- Art Supplies

- Easels

- Badge Holder & Accessories

- Office Paper

- Printer Supplies

- Book Covers

- Other Office & School Supplies

- Stationery Set

- Boards

- Clipboards

- Stamps

- Drafting Supplies

- Stencils

- Electronic Dictionary

- Books

- Map

- Magazines

- Calculators

- Baby & Toddler Toys

- Educational Toys

- Classic Toys

- Dress Up & Pretend Play

- Toy Vehicle

- Stuffed Animals & Plush Toys

- Outdoor Toys & Structures

- Balloons & Accessories

- Baby Food

- Children's Clothing

- Baby Supplies & Products

- Maternity Clothes

- Kids Shoes

- Baby Care

- Novelty & Gag Toys

- Dolls & Accessories

- Puzzle & Games

- Blocks & Model Building Toys

- Toddler Clothing

- Baby Clothing

- Kids' Luggage & Bags

- Arts, Crafts & DIY Toys

- Action & Toy Figures

- Baby Appliances

- Hobbies & Models

- Remote Control Toys

- Promotional Toys

- Pregnancy & Maternity

- Hygiene Products

- Kid's Textile&Bedding

- Novelty & Special Use

- Toy Weapons

- Baby Gifts

- Baby Storage & Organization

- Auto Drive Systems

- ATV/UTV Parts & Accessories

- Marine Parts & Accessories

- Other Auto Parts

- Trailer Parts & Accessories

- Auto Transmission Systems

- Train Parts & Accessories

- Universal Parts

- Railway Parts & Accessories

- Auto Brake Systems

- Aviation Parts & Accessories

- Truck Parts & Accessories

- Auto Suspension Systems

- Auto Lighting Systems

- New Energy Vehicle Parts & Accessories

- Auto Steering Systems

- Wheels, Tires & Accessories

- Bus Parts & Accessories

- Auto Performance Parts

- Cooling System

- Go-Kart & Kart Racer Parts & Accessories

- Air Conditioning Systems

- Heavy Duty Vehicle Parts & Accessories

- Auto Electrical Systems

- Auto Body Systems

- Auto Engine Systems

- Container Parts & Accessories

- Motorcycle Parts & Accessories

- Refrigeration & Heat Exchange Equipment

- Machine Tool Equipment

- Food & Beverage Machinery

- Agricultural Machinery & Equipment

- Apparel & Textile Machinery

- Chemical Machinery

- Packaging Machines

- Paper Production Machinery

- Plastic & Rubber Processing Machinery

- Industrial Robots

- Electronic Products Machinery

- Metal & Metallurgy Machinery

- Woodworking Machinery

- Home Product Manufacturing Machinery

- Machinery Accessories

- Environmental Machinery

- Machinery Service

- Electrical Equipment Manufacturing Machinery

- Industrial Compressors & Parts

- Tobacco & Cigarette Machinery

- Production Line

- Used Industrial Machinery

- Electronics Production Machinery

- Other Machinery & Industrial Equipment

- Camera, Photo & Accessories

- Portable Audio, Video & Accessories

- Television, Home Audio, Video & Accessories

- Video Games & Accessories

- Mobile Phone & Accessories

- Electronic Publications

- Earphone & Headphone & Accessories

- Speakers & Accessories

- Smart Electronics

- TV Receivers & Accessories

- Mobile Phone & Computer Repair Parts

- Chargers, Batteries & Power Supplies

- Used Electronics

- VR, AR, MR Hardware & Software

- Projectors & Presentation Equipments

- Other Consumer Electronics

- Cables & Commonly Used Accessories

- Computer Hardware & Software

- Displays, Signage and Optoelectronics

- Discrete Semiconductors

- Wireless & IoT Module and Products

- Telecommunications

- Connectors, Terminals & Accessories

- Development Boards, Electronic Modules and Kits

- Circuit Protection

- Sensors

- Isolators

- Audio Components and Products

- Integrated Circuits

- Power Supplies

- Relays

- RF, Microwave and RFID

- Electronic Accessories & Supplies

- Passive Components

- PCB & PCBA

- Air Quality Appliances

- Home Appliance Parts

- Heating & Cooling Appliances

- Small Kitchen Appliances

- Laundry Appliances

- Water Heaters

- Water Treatment Appliances

- Refrigerators & Freezers

- Personal Care & Beauty Appliances

- Major Kitchen Appliances

- Cleaning Appliances

- Second-hand Appliances

- Smart Home Appliances

- Other Home Appliances

- Energy Chemicals

- Inorganic Chemicals

- Basic Organic Chemicals

- Agrochemicals

- Admixture & Additives

- Catalysts & Chemical Auxiliary Agents

- Pigments & Dyestuff

- Coating & Paint

- Daily Chemicals

- Polymer

- Organic Intermediate

- Adhesives & Sealants

- Chemical Waste

- Biological Chemical Products

- Surface Treatment Chemicals

- Painting & Coating

- Chemical Reagents

- Flavor & Fragrance

- Non-Explosive Demolition Agents

- Other Chemicals

- Custom Chemical Services

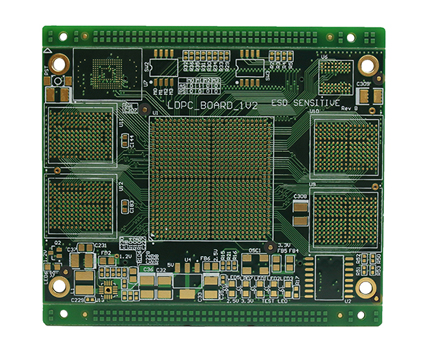

The Critical Role Of High Frequency PCBs In Enabling 5G Networks Satellite Communications And Cutting Edge Radar Systems Worldwide

In the rapidly evolving landscape of global telecommunications and defense technology, a silent yet pivotal enabler works behind the scenes: the high-frequency printed circuit board (PCB). As the world races toward ubiquitous 5G connectivity, expands satellite communication networks, and develops next-generation radar systems, the demand for electronics that can operate reliably at millimeter-wave frequencies has skyrocketed. High-frequency PCBs are not merely incremental improvements over their conventional counterparts; they are specialized substrates engineered to manage signals in the gigahertz (GHz) range and beyond with minimal loss and distortion. This article delves into the critical role these advanced circuit boards play in powering the infrastructure of modern connectivity and sensing, exploring the material science, design challenges, and transformative applications that make them indispensable to our interconnected, data-driven world.

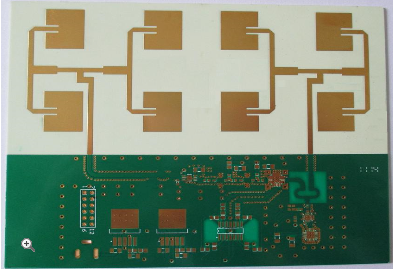

The Material Foundation: Engineered Substrates for Minimal Signal Loss

The performance of high-frequency PCBs is fundamentally dictated by their substrate materials. Unlike standard FR-4 boards used in everyday electronics, high-frequency applications require laminates with exceptionally low dielectric constant (Dk) and dissipation factor (Df). Materials like polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE/Teflon), ceramic-filled hydrocarbons, and specialized epoxy blends are commonly employed. These materials ensure that the signal propagation speed remains high and that energy loss, manifested as heat, is minimized. This is crucial because at frequencies above 1 GHz, even minor losses can degrade signal integrity, leading to reduced range, data errors, and system inefficiency.

Furthermore, the thermal stability of these materials is paramount. High-frequency circuits, especially those in power amplifiers for 5G base stations or radar transmitters, generate significant heat. The substrate must maintain consistent electrical properties across a wide temperature range to prevent performance drift. Manufacturers also pay meticulous attention to the copper foil used, often opting for low-profile or reverse-treated foils to reduce surface roughness, which can cause additional signal loss at high frequencies due to the skin effect, where current flows primarily on the conductor's surface.

Design and Manufacturing Precision: Navigating the Challenges of GHz Frequencies

Designing a high-frequency PCB is an exercise in precision electromagnetics. At microwave and millimeter-wave frequencies, circuit traces behave less like simple wires and more like transmission lines. Impedance control becomes a non-negotiable design criterion. Every trace, bend, and via must be meticulously calculated and fabricated to maintain a specific characteristic impedance (typically 50 or 75 ohms) to prevent signal reflections that can cause standing waves and cripple performance. This requires advanced simulation software and a deep understanding of electromagnetic field theory.

The manufacturing process itself is equally demanding. Tight tolerances for trace width, spacing, and dielectric thickness are essential. Any variation can alter the impedance and degrade the circuit's function. Techniques like laser drilling for micro-vias and plasma etching for precise surface treatment are standard. Layer-to-layer registration must be flawless, particularly in complex multilayer boards used in phased-array antennas. The entire fabrication process occurs in a tightly controlled environment to prevent contamination that could affect the substrate's electrical properties, making the production of high-frequency PCBs a specialized and highly technical endeavor.

Enabling the 5G Revolution: From Base Stations to User Equipment

The rollout of 5G networks, particularly the high-bandwidth, high-speed millimeter-wave (mmWave) spectrum, is perhaps the most visible driver for high-frequency PCB technology. 5G base stations, especially massive MIMO (Multiple Input, Multiple Output) antennas, rely on dense arrays of transceivers. Each element in this array requires its own high-frequency RF front-end, built on PCBs that can handle frequencies from 24 GHz to 39 GHz and potentially higher. These PCBs enable the beamforming and beam-steering technologies that allow 5G to direct focused data streams to individual users, dramatically increasing network capacity and speed.

Beyond the infrastructure, high-frequency PCBs are also finding their way into user equipment. While smartphone internal antennas are highly integrated, the test equipment, prototyping boards, and emerging devices like fixed wireless access (FWA) terminals all depend on these advanced substrates. They allow for the miniaturization of complex RF circuits while maintaining the signal integrity necessary for multi-gigabit data rates, making the promise of 5G a practical reality.

Connecting the Globe: The Backbone of Satellite Communications

Satellite communication systems, essential for global broadcasting, remote sensing, and bridging the digital divide, operate in even higher frequency bands, such as Ku-band (12-18 GHz), Ka-band (26.5-40 GHz), and V-band (40-75 GHz). High-frequency PCBs are the foundation of the low-noise block downconverters (LNBs) in satellite dishes, the transponders onboard the satellites themselves, and the ground station equipment. In these applications, signal loss is the enemy, as the signals travel thousands of kilometers through space.

The PCBs used here must exhibit not only excellent electrical performance but also outstanding reliability in harsh environmental conditions. Satellites face extreme thermal cycling, vacuum, and radiation. Terrestrial equipment must withstand temperature variations, humidity, and corrosion. High-frequency laminates are selected and tested rigorously for these conditions. Furthermore, the push for low-earth orbit (LEO) satellite constellations for global internet coverage demands lightweight, high-performance, and cost-effective RF hardware, placing further innovation pressure on PCB manufacturers to deliver robust solutions that can be produced at scale.

Powering Advanced Radar and Defense Systems

In the realm of defense, aerospace, and automotive safety, cutting-edge radar systems are critical for detection, imaging, and navigation. Modern radar, including automotive ADAS (Advanced Driver-Assistance Systems) radar and military-grade phased array radar, operates at high frequencies (e.g., 77 GHz for automotive) to achieve fine resolution and accurate target discrimination. The heart of these systems is an active electronically scanned array (AESA), which consists of hundreds or thousands of tiny transmit/receive modules.

Each of these modules is built upon a high-frequency PCB that integrates antennas, power amplifiers, low-noise amplifiers, and phase shifters into a compact unit. The PCB material must allow for the precise control of signal phase and amplitude across the entire array to electronically steer the radar beam without moving parts. This capability is vital for applications like fighter jet radars, missile guidance, and weather monitoring, where speed, reliability, and accuracy are paramount. The durability and performance consistency of the PCB under vibration, shock, and thermal stress directly translate to the system's operational readiness and effectiveness.

In conclusion, high-frequency PCBs are far more than just circuit boards; they are the fundamental physical layer upon which the most advanced wireless technologies of our time are built. From the dense urban landscapes lit up by 5G to the satellites orbiting overhead and the radar systems safeguarding nations, these engineered substrates enable the precise manipulation of electromagnetic waves that define modern communication and sensing. As the demand for higher bandwidth, lower latency, and greater connectivity continues to grow, the innovation in high-frequency PCB materials, design, and manufacturing will remain at the forefront, quietly but critically shaping our technological future.

REPORT